What Are Math Fact Strategies? How They Help Your Child Learn Faster

Let me ask you a Math question. Ready?

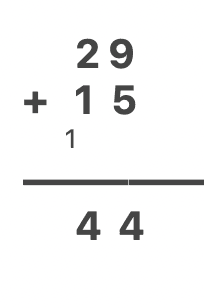

What is 29 + 15?

Go ahead. Guess. Scroll only after you have a guess.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Did you guess 44? Ok good. If not, that's ok too.

Now - how did you know it was 44 (or any other number you guessed)? How exactly did you do it?

At this point, a lot of you might say "I just knew it" or "it just came to me" - but I will push you to really think about it.

Some of you may have used the standard method -

Some others might have done "30 + 15 is 45 - minus 1 (since 30 is 1 more than 29) -> equals 44".

Some others still might have done - 29 + 10 is 39, and then +5 = 44.

Maybe even - 29 + 20 = 49 - and then 49 - 5 = 44 (since 20 is 5 more than 15).

If you don't believe this, just ask this question to a group of people around you and then individually ask them "how exactly did they do it". I'm 100% sure you'll be surprised by the variety of answers you hear.

What exactly is a strategy?

Now what was the point of the above exercise? And why in the world would some people "complicate" the problem by making it multi-step, rather than just doing it the standard way?

That's because, some of these steps that look more complicated when written out - are actually more efficient to do in the brain. They rely on properties of some numbers that make adding/subtracting/multiplying or dividing with them much easier, as well as properties of the operations themselves, that let you convert unfriendly math facts into friendlier ones.

In a nutshell, a Math fact strategy generally allows you to convert seemingly unfriendly or difficult math facts into something that's easier, allowing you to perform that operation much more easily.

What Are Math Strategies *Not*? Common Misunderstandings

A Strategy is not a fixed procedure - if you expect kids or even adults to just rote-learn the different strategies, it just defeats the purpose of using them in the first place. You might as well rote-learn basic facts and never have to use the strategies again.

The strategies are useful when you can derive them on the fly - mentally - as and when required - because you intimately understand the math operations.

Strong Grasp Of Concepts And Strong Working Memory

For instance - in the example above -

"30 + 15 is 45 - minus 1 (since 30 is 1 more than 29) -> equals 44".

The person coming up with this way of doing 29 + 15 needs to already know many things.

- It's easier to add something to a multiple of 10 (such as 30) than to a number ending with 9 (such as 29)

- If you add a 1 to the first operand, and add another number to it, to get the final answer you have to again remove 1.

Basically you are doing this - 29 + 15 = (+1 + 29) + 15 - 1.

But instead of having to write this down explicitly, the person understands it intuitively. - 30 + 15 = 45 -> this is just an addition problem without carryover, so it's much easier to do in the head.

- 45 - 1 is the previous number = 44.

- The learner also needs enough working memory to hold all the above steps in their head. If by the time they have done 30 + 15 = 45, they forget that they had added an extra 1 and so they have to remove that - they will end up with the wrong answer.

So even with good Math Fact fluency, strong working memory is super helpful in doing Mental Math calculations.

Learn more about how working memory affects math for kids with ADHD.

It's the knowing of some of these basic properties of numbers and addition operation that allows the person to use a more efficient strategy in their head and change the unfriendly problem to a friendly one.

This is why teachers or parents should never focus on helping kids memorise the strategies. Having questions in a worksheet where you expect a specific strategy to be used can be counter productive - it doesn't allow the learner to play around with numbers and arrive at their own strategies.

What can work is Number Talks. Seeing other kids coming up with different strategies often expand a child's mind. Here is a really good video from Dr. Jo Boaler about Number Talks and how to do it.

Explicit Strategy Instruction

Now the question arises. Why do different people use different strategies for the same problem? And why do some people just end up using the standard method even if a different method would be faster/easier to do mentally?

The answer is - we haven't really had a lot of explicit Math Strategy instruction in our classrooms. Kids who sort of "get it" - they get it intuitively and seem to be really fast. We call these kids "good at math".

The kids who don't - try to use the same standard methods faster and faster in their heads. But that just doesn't work! A child trying to do 119 + 94 in their head, using the standard method will always struggle, whereas a person who can quickly do "120 + 100 = 220 minus 1 minus 6 = 213" - will end up doing it much faster. This is why kids who don't become flexible with numbers then get the feeling "they are bad at Math".

Whereas the problem has always been - to use an analogy - they've been using a bicycle in a motorcycle race.

This can be avoided by using explicit Strategy Instruction. The aim is again - not to have kids rote-learn the strategies - but expose them to it in so many ways and helping them grasp the fundamentals so well, that they can come up with a strategy to simplify tough problems on the fly.

Dr. Jennifer Bay William's book on Math Fact Fluency is an excellent primer on the different Math strategies and how to go about them.

Example of Good Math Fact Instruction

For example, in traditional classroom learning, we always rote-learn tables of 1, 2, 3 and so on, till about 10 or 12. However, it makes more sense to first do tables that are easier - tables of 1, tables of 2, tables of 5 and 10. These are the easiest because the patterns are simple for kids to understand.

Then you can move to tables of 4, 6 and 9, which can be memorised- but can also be derived from the simpler tables. For e.g. 4 X 6 is nothing but 5 X 6 - 6; so if the child remembers 5 X 6, they can do 30 - 6 = 24.

We've listed 5 ADHD-friendly math games that are great for your child, especially if have ADHD.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are math fact strategies?

They are flexible mental math techniques that help learners solve problems more efficiently by using number relationships—like turning 29 + 15 into 30 + 15 and subtracting 1.

Are math strategies better than memorizing facts?

Yes. Strategies develop number sense and help kids understand how math works, while memorization without understanding leads to shallow fluency that doesn’t support higher-level math.

How do I teach my child math strategies?

Start with number talks—ask your child *how* they got an answer, not just what it is. Then build in strategy games and activities that develop flexibility, not speed.

Next Steps: Bring Math Strategies into Daily Life

The first step would be Number Talks. Try to elicit how exactly your child is doing the operations, rather than just getting the answer. If you can do this in a group where different kids/people can come up with different answers, it's even better - that will allow your child to get exposed to different methods in a friendly way.

Once you know what kind of strategies your child is using - whether the most basic ones combined with standard but inefficient methods, or more advanced ones, you can combine that with explicit strategy practice. Jennifer's book gives lots of ideas on Math games to play at home for these.

You can also try out Monster Math which embeds a lot of this strategy instruction in a fun game format. Your child visually sees how Math works, while learning foundational and advanced Math fact strategies and developing Math fact fluency. And it comes with a risk-free 7-day Trial, so you can always see if it works for your child or not before committing to it!

Comments

Your comment has been submitted